Paper:

The Effect of Pay-It-Forward During Disasters on Social Networks: A Network Approach

Riku Tanimoto*,† and Hitomu Kotani**

*Department of Urban Management, Graduate School of Engineering, Kyoto University

C1 Kyotodaigaku-Katsura, Nishikyo-ku, Kyoto, Kyoto 615-8540, Japan

†Corresponding author

**Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, School of Environment and Society, Tokyo Institute of Technology

Tokyo, Japan

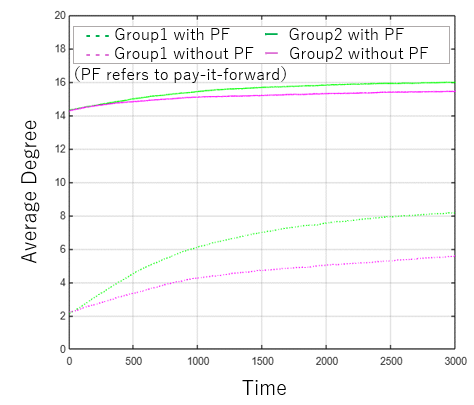

Some disaster survivors who had previously received support through volunteering participated in volunteer activities for people affected by subsequent disasters. This chain of support, known as “pay-it-forward,” is expected to expand social networks and bring about small-world property (i.e., networks with high clustering and short path length between people). Previous research has focused on the effects of pay-it-forward on individuals (i.e., the psychological perspective), but has insufficiently determined its effects on the whole society or social networks (i.e., the sociological perspective). This study investigates the dynamic effects of pay-it-forward on network properties. We proposed a network formation model considering pay-it-forward during disasters and conducted numerical simulations. The results showed that pay-it-forward led to small-world property and higher social welfare in the long term, because it eliminated the disparity in ties between people (in particular, it reduced the number of people with fewer ties), which accelerated network formation during non-disaster periods. This result was more pronounced in societies with a larger disparity in ties. From a sociological perspective, our findings imply the significance of pay-it-forward volunteering and volunteer organizations that promote such activities.

The degree disparities elimination effect

- [1] T. Atsumi, “Relaying support in disaster affected areas: The social implications of a ‘pay-it-forward’ network,” Disasters, Vol.38, No.s2, pp. s144-s156, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1111/disa.12067

- [2] M. A. Nowak and S. Karl, “Evolution of indirect reciprocity,” Nature, Vol.437, No.7063, pp. 1291-1298, 2005. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04131

- [3] H. Daimon and T. Atsumi, “Constructing a positive circuit of debt among survivors: An action research study of disaster volunteerism in Japan,” Natural Hazards, Vol.105, pp. 461-480, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-020-04319-8

- [4] T. Uchio, “The dawn of public anthropology after the Great East Japan Earthquake,” Japanese Society of Cultural Anthropology, Vol.78, No.1, pp. 99-110, 2013 (in Japanese). https://doi.org/10.14890/jjcanth.78.1_99

- [5] H. Daimon and T. Atsumi, “‘Pay it forward’ and altruistic responses to disasters in Japan: Latent class analysis of support following the 2011 Tohoku earthquake,” VOLUNTAS: Int. J. of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, Vol.29, pp. 119-132, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-017-9880-y

- [6] H. Mitani, “Disaster response volunteering as a generalized exchange: Empirical analysis of the phenomenon of relay between affected areas,” Sociological Theory and Methods, Vol.30, No.1, pp. 69-83, 2015 (in Japanese). https://doi.org/10.11218/ojjams.30.69

- [7] S. Obayashi et al., “It’s my turn: Empirical evidence of upstream indirect reciprocity in society through a quasi-experimental approach,” J. of Computational Social Science, Vol.6, No.2, pp. 1055-1079, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42001-023-00221-y

- [8] D. J. Watts and S. H. Strogatz, “Collective dynamics of ‘small-world’ networks,” Nature, Vol.393, No.6684, pp. 440-442, 1998. https://doi.org/10.1038/30918

- [9] M. A. Nowak and R. Sébastien, “Upstream reciprocity and the evolution of gratitude,” Proc. of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, Vol.274, No.1610, pp. 605-610, 2007. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2006.0125

- [10] A. Iwagami and N. Masuda, “Upstream reciprocity in heterogeneous networks,” J. of Theoretical Biology, Vol.265, No.3, pp. 297-305, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtbi.2010.05.010

- [11] Y.-S. Chiang and N. Takahashi, “Network homophily and the evolution of the pay-it-forward reciprocity,” PLOS One, Vol.6, No.12, Article No.e29188, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0029188

- [12] Z. Q. Jiang et al., “Unraveling the effects of network, direct and indirect reciprocity in online societies,” Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, Vol.169, Article No.113276, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2023.113276

- [13] Z. Chen and J. Guan, “The impact of small world on innovation: An empirical study of 16 countries,” J. of Informetrics, Vol.4, No.1, pp. 97-106, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2009.09.003

- [14] L. Lü et al., “The small world yields the most effective information spreading,” New J. of Physics, Vol.13, No.12, Article No.123005, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/13/12/123005

- [15] P. V. Singh, “The small-world effect: The influence of macro-level properties of developer collaboration networks on open-source project success,” ACM Trans. on Software Engineering and Methodology, Vol.20, No.2, pp. 1-27, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1145/1824760.1824763

- [16] H. Kotani and M. Yokomatsu, “Natural disasters and dynamics of “a paradise built in hell”: A social network approach,” Natural Hazards, Vol.84, pp. 309-333, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-016-2432-8

- [17] M. O. Jackson and A. Watts, “The evolution of social and economic networks,” J. of Economic Theory, Vol.106, No.2, pp. 265-295, 2002. https://doi.org/10.1006/jeth.2001.2903

- [18] J. S. Coleman, “Social capital in the creation of human capital,” American J. of Sociology, Vol.94, pp. s95-s120, 1988.

- [19] V. Latora and M. Marchiori, “Efficient behavior of small-world networks,” Physical Review Letters, Vol.87, No.19, Article No.198701, 2001. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.87.198701

- [20] M. O. Jackson, “Social and Economic Networks,” Princeton University Press, 2008.

- [21] E. J. M. Newman, “Networks: An Introduction,” Oxford University Press, pp. 181-185, 2010.

- [22] M. McPherson, L. Smith-Lovin, and J. M. Cook, “Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks,” Annual Review of Sociology, Vol.27, No.1, pp. 415-444, 2001.

- [23] M. O. Jackson, “Inequality’s economic and social roots: The role of social networks and homophily,” SSRN Electronic J., 2021. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3795626

- [24] D. Y. Jung and K.-M. Ha, “A comparison of the role of voluntary organizations in disaster management,” Sustainability, Vol.13, No.4, Article No.1669, 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041669

- [25] E. Ntontis et al., “Endurance or decline of emergent groups following a flood disaster: Implications for community resilience,” Int. J. of Disaster Risk Reduction, Vol.45, Article No.101493, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101493

- [26] R. Solnit, “A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities That Arise in Disaster,” Penguin, 2010.

- [27] H. Daimon and T. Atsumi, “Simulating disaster volunteerism in Japan: ‘Pay it forward’ as a strategy for extending the post-disaster altruistic community,” Natural Hazards, Vol.93, pp. 699-713, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-018-3309-9

This article is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 Internationa License.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 Internationa License.