Paper:

Flood Risk Perception in an Inherently Flood-Prone Urban Area: Based on a Land Price Analysis in the Arakawa River Downstream Area, Tokyo

Kozo Nagami*,†

, Ryo Inoue**

, Ryo Inoue**

, and Daisuke Komori*

, and Daisuke Komori*

*Green Goals Initiative, Tohoku University

E501, IRIDeS, 468-1 Aramaki Aza-Aoba, Aoba-ku, Sendai, Miyagi 980-0845, Japan

†Corresponding author

**Graduate School of Information Sciences, Tohoku University

Sendai, Japan

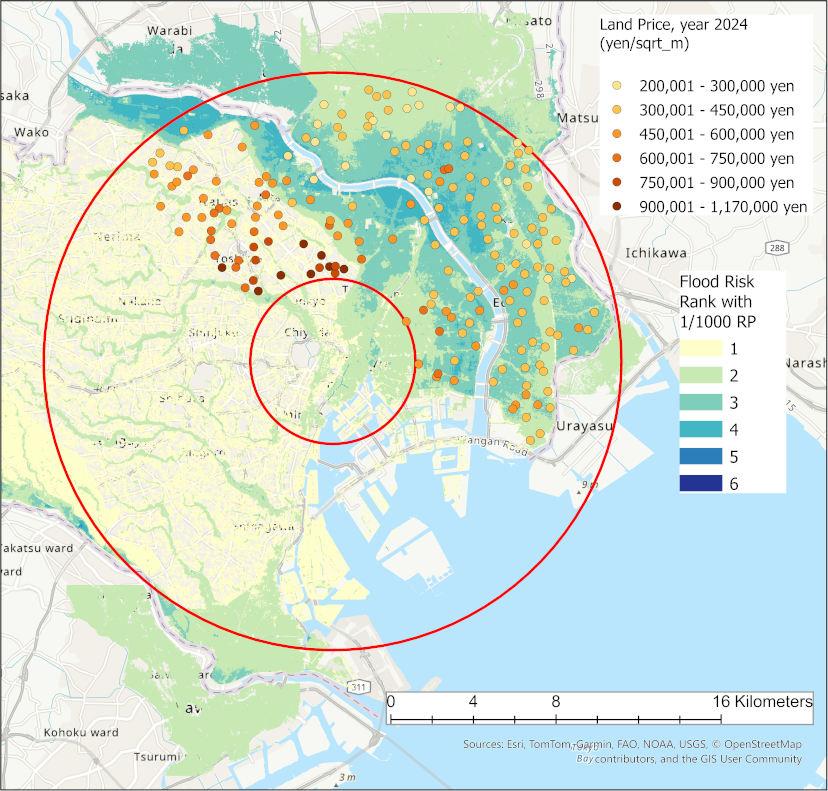

In urban developments, inherently flood-prone areas are often developed to pursue economic benefits within land constraints. This trend has been observed worldwide, particularly in fast-growing developing countries, but has also historically occurred in developed nations, resulting in concerns about the safe development paradox and underestimation of flood risk. If these circumstances are persistently entrenched and difficult to improve, urban development in inherently flood-prone areas could be an irreversible bottleneck to sustainable urban development. This paper examines flood risk perception in the Arakawa River downstream area in Tokyo by analyzing land prices from 2005 to 2024. Over these 20 years, the official flood hazard map was legally set at the design flood level in 2005 and enhanced to the probable maximum flood level in 2015. The analysis showed statistically significant land price decline effects due to both design flood risk and probable maximum flood risk, regardless of inundation rank. This result confirmed that flood risk has been well perceived by society and residents at least over the 20 years in the area. Further analysis suggested that even before 2015, land prices significantly reflected probable maximum flood risk, likely due to past experiences. However, the 2015 legal revision of the flood hazard map amplified land price decline effects in areas with high probable maximum flood risk (above 5.0 meters of inundation). The results indicate that hazard maps can serve as effective disaster risk information tools to support sustainable urban development.

Official land price and flood hazard map

- [1] “Global assessment report on disaster risk reduction,” United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR), 2015. https://www.undrr.org/publication/global-assessment-report-disaster-risk-reduction-2015 [Accessed June 18, 2024]

- [2] “Global assessment report on disaster risk reduction,” UNDRR, 2019. https://www.undrr.org/publication/global-assessment-report-disaster-risk-reduction-2019 [Accessed June 18, 2024]

- [3] W. Kron, “Flood Risk = Hazard · Values · Vulnerability,” Water Int., Vol.30, Issue 1, pp. 58-68, 2005. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060508691837

- [4] B. Tellman, J. A. Sullivan, C. Kuhn, A. J. Kettner, C. S. Doyle, G. R. Brakenridge, T. A. Erickson, and D. A. Slayback, “Satellite imaging reveals increased proportion of population exposed to floods,” Nature, Vol.596, pp. 80-86, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03695-w

- [5] B. Schultz, “Flood management under rapid urbanisation and industrialisation in flood-prone areas: A need for serious consideration,” Irrigation and Drainage, Vol.55, Issue S1, pp. s3-s8, 2006. https://doi.org/10.1002/ird.237

- [6] L. Weinstein, A. Rumbach, and S. Sinha, “Resilient growth: Fantasy plans and unplanned developmnets in India’s flood-prone coastal cities,” Int. J. of Urban and Regional Research, Vol.43, Issue 2, pp. 273-291, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12743

- [7] Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED) and UNDRR, “2020: The non-COVID year in disasters,” CRED, 2021. http://www.undrr.org/quick/13439 [Accessed June 18, 2024]

- [8] P. Hudson and W. J. W. Botzen, “Cost-benefit analysis of flood-zoning policies: A review of current practice,” WIREs Water, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1002/wat2.1387

- [9] A. M. Juarez-Lucas, K. M. Kibler, T. Sayama, and M. Ohara, “Flood risk-benefit assessment to support management of flood prone lands,” J. Flood Risk Management, Vol.19, Issue 3, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfr3.12476

- [10] M. R. Stevens, Y. Song, and P. R. Berke, “New Urbanist developments in flood-prone areas: safe development, or safe development paradox?,” Natural Hazards, Vol.53, pp. 605-629, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-009-9450-8

- [11] Y. Takahasi and J. I. Uitto, “Evolution of river management in Japan: From focus on economic benefits to a comprehensive view,” Global Environmental Change, Vol.14, Supplement, pp. 63-70, 2004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2003.11.005

- [12] N. Nirupama and S. P. Simonovic, “Increase of flood risk due to urbanisation: A Canadian example,” Natural Hazards, Vol.40, pp. 25-41, 2007. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-006-0003-0

- [13] A. Mustafa, M. Bruwier, P. Archambeau, S. Erpicum, M. Pirotton, B. Dewals, and J. Teller, “Effects of spatial planning on future flood risks in urban environments,” J. of Environmental Management, Vol.225, pp. 193-204, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.07.090

- [14] UNDRR, “Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction 2015–2030,” 2015. https://www.undrr.org/publication/sendai-framework-disaster-risk-reduction-2015-2030 [Accessed June 18, 2024]

- [15] C. M. Shreve and I. Kelman, “Does mitigation save? Reviewing cost-benefit analyses of disaster risk reduction,” Int. J. of Disaster Risk Reduction, Vol.10, Part A, pp. 213-235, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2014.08.004

- [16] R. Mechler, “Reviewing estimates of the economic efficiency of disaster risk management: Opportunities and limitations of using risk-based cost–benefit analysis,” Natural Hazards, Vol.81, pp. 2121-2147, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-016-2170-y

- [17] T. Doeffinger and S. Rubinyi, “Secondary benefits of urban flood protection,” J. of Environmental Management, Vol.326, Part A, Article No.116617, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.116617

- [18] W. J. Wouter Botzen, O. Deshenes, and M. Sanders, “The economic impacts of natural disasters: A review of models and empirical studies,” Review of Environmental Economics and Policy, Vol.13, Issue 2, pp. 167-188, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1093/reep/rez004

- [19] K. H. Liao, “A theory on urban resilience to floods—A basis for alternative planning practices,” Ecology and Society, Vol.17, No.4, Article No.48, 2012. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-05231-170448

- [20] G. Di Baldassarre, M. Sivapalan, M. Rusca, C. Cudennec, M. Garcia, H. Kreibich, M. Konar, E. Mondino, J. Mård, S. Pande, M. R. Sanderson, F. Tian, A. Viglione, J. Wei, Y. Wei, D. J. Yu, V. Srinivasan, and G. Blöschl, “Socio hydrology: Scientific challenges in addressing the sustainable development goals,” Water Resources Research, Vol.55, Issue 8, pp. 6327-6355, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018WR023901

- [21] Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, “Regarding flood control measures for disaster mitigation in response to large-scale floods (Preceeding report),” 2015 (in Japanese). https://www.mlit.go.jp/common/001113051.pdf [Accessed June 21, 2024]

- [22] R. Inoue, M. Nagayoshi, and D. Komori, “Detecting a change-point of flood risk influence on land prices,” J. of Japan Society of Civil Engineers Ser. B1 (Hydraulic Engineering), Vol.72, Issue 4, pp. I_1309-I_1314, 2016 (in Japanese). https://doi.org/10.2208/jscejhe.72.I_1309

- [23] Y. Sado-Inamura and K. Fukushi, “Empirical analysis of flood risk perception using historical data in Tokyo,” Land Use Policy, Vol.82, pp. 13-29, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.11.031

- [24] R. Inoue and K. Hatori, “How does residential property market react to flood risk in flood-prone regions? A case study in Nagoya city,” Frontiers in Water, Vol.3, Article No.661662, 2021. https://doi.org/10.3389/frwa.2021.661662

- [25] A. Atreya, S. Ferreira, and W. Kriesel, “Forgetting the flood? An analysis of the flood risk discount over time,” Land Economics, Vol.89, No.4, pp. 577-596, 2013.

- [26] E. Saputra, I. S. Ariyanto, R. A. Ghiffari, and M. S. I. Fahmi, “Land value in a disaster-prone urbanized coastal area: A case study from Semarang City, Indonesia,” Land, Vol.10, Issue 11, Article No.1187, 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10111187

- [27] F. Ortega and S. Taşpınar, “Rising sea levels and sinking property values: Hurricane Sandy and New York’s housing market,” J. of Urban Economics, Vol.106, pp. 81-100, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2018.06.005

- [28] A. Votsis and A. Perrels, “Housing prices and the public disclosure of flood risk: A difference-in-differences analysis in Finland,” J. of Real Estate Finance and Economics, Vol.53, pp. 450-471, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-015-9530-3

- [29] “Digital National Land Information,” National Spatial Planning and Regional Policy Bureau, MLIT of Japan (in Japanese). https://nlftp.mlit.go.jp/ksj/ [Accessed March 19, 2025]

This article is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 Internationa License.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 Internationa License.