Paper:

Analyzing Two Approaches in Interdisciplinary Research: Individual and Collaborative

Masanori Fujita*1,†, Takato Okudo*2, Takao Terano*3, and Hiromi Nagane*4

*1The National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies

7-22-1 Roppongi, Minato-ku, Tokyo 106-8677, Japan

*2The Graduate University for Advanced Studies (SOKENDAI)

2-1-2 Hitotsubashi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 101-8430, Japan

*3Chiba University of Commerce

1-3-1 Konodai, Ichikawa-City, Chiba 272-8512, Japan

*4Chiba University

1-33 Yayoi-cho, Inageku, Chiba-City, Chiba 263-8522, Japan

†Corresponding author

We propose a method for measuring interdisciplinary research by dividing it into two approaches: interdisciplinary research conducted by individual researchers and interdisciplinary research involving the collaboration of multiple researchers. Using this method, a database of “KAKENHI,” which is a grant-in-aid for scientific research provided by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), is employed to measure interdisciplinary research from the perspective of the two research approaches, and the features of interdisciplinary research in KAKENHI are analyzed. The analysis results indicate the following: (1) the number of collaborative interdisciplinary research projects is larger than the number of individual interdisciplinary research projects, (2) the number of interdisciplinary research projects for each field and for each combination of fields differs among fields, and (3) the relationship between the numbers of interdisciplinary research projects in the two fields is asymmetric with regard to the main- and sub-fields of interdisciplinary research. As the proposed measurement method is capable of quantitatively measuring interdisciplinarity between fields and their research organizations, it will be useful for decision-makers in science and technology policy and strategy.

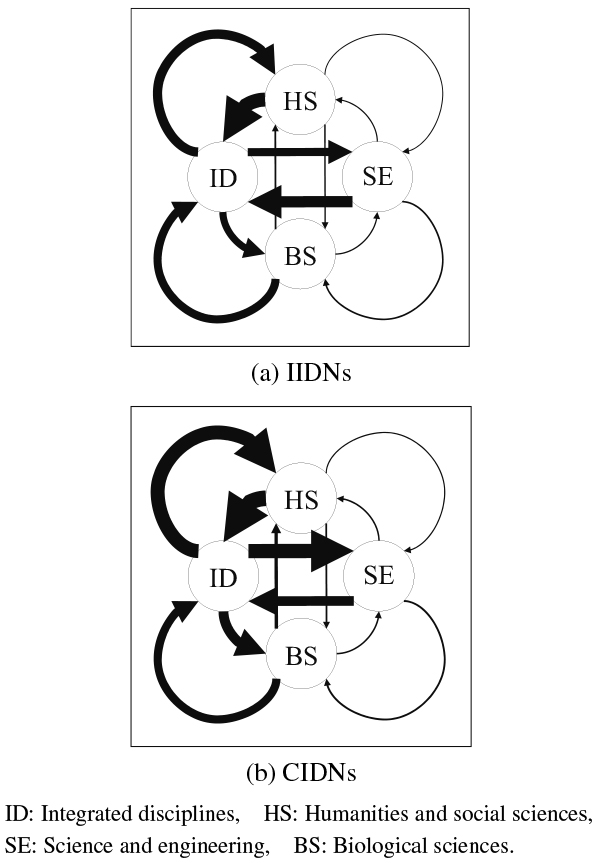

Relationship between Main-Fields and Sub-Fields of individual interdisciplinary networks (IIDNs) and collaborative interdisciplinary networks (CIDNs) in Scientific Research (A) of KAKENHI

- [1] J. G. March, “Exploration and Exploitation in Organizational Learning,” Organization Science, Vol.2, No.1, pp. 71-87, 1991.

- [2] A. Stirling, “A general framework for analysing diversity in science, technology and society,” J. of the Royal Society Interface, Vol.4, No.15, pp. 707-719, 2007.

- [3] I. Rafols and M. Meyer, “Diversity and network coherence as indicators of interdisciplinarity: case studies in bionanoscience,” Scientometrics, Vol.82, No.2, pp. 263-287, 2010.

- [4] L. Leydesdorff and I. Rafols, “A Global Map of Science Based on the ISI Subject Categories,” J. of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, Vol.60, No.2, pp. 348-362, 2009.

- [5] I. Rafols, A. L. Porter, and L. Leydesdorff, “Science Overlay Maps: A New Tool for Research Policy and Library Management,” J. of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, Vol.61, No.9, pp. 1871-1887, 2010.

- [6] I. Rafols, L. Leydesdorff, A. O’Hare et al., “How journal rankings can suppress interdisciplinary research: A comparison between Innovation Studies and Business & Management,” Research Policy, Vol.41, No.7, pp. 1262-1282, 2012.

- [7] X. Sun, K. Ding, and Y. Lin, “Mapping the evolution of scientific fields based on cross-field authors,” J. of Informetrics, Vol.10, No.3, pp. 750-761, 2016.

- [8] A. Kastrin, J. Klisara, B. Luzar et al., “Is science driven by principal investigators?,” Scientometrics, Vol.117, No.2, pp. 1157-1182, 2018.

- [9] G. Abramo, C. A. D’Angelo, and F. Di Costa, “Specialization versus diversification in research activities: the extent, intensity and relatedness of field diversification by individual scientists,” Scientometrics, Vol.112, No.3, pp. 1403-1418, 2017.

- [10] A. L. Porter and I. Rafols, “Is science becoming more interdisciplinary? Measuring and mapping six research fields over time,” Scientometrics, Vol.81, No.3, pp. 719-745, 2009.

- [11] S. Chen, C. Arsenault, Y. Gingras et al., “Exploring the interdisciplinary evolution of a discipline: the case of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology,” Scientometrics, Vol.102, No.2, pp. 1307-1323, 2015.

- [12] D. Crane, “Invisible Colleges: Diffusion of Knowledge in Scientific Communities,” The University of Chicago, 1972.

- [13] T. J. Allen, “Managing the Flow of Technology,” MIT Press, 1979.

- [14] M. E. J. Newman, “Coauthorship networks and patterns of scientific collaboration,” Proc. of the National Academy of Sciences, Vol.101, Suppl. 1, pp. 5200-5205, 2004.

- [15] K. Shinoda, “A Family Tree of Artificial Intelligence Research in Japan,” J. of Japanese Society for Artificial Intelligence, Vol.26, No.6, pp. 584-589, 2011 (in Japanese).

- [16] S. Narayanan, J. M. Swaminathan, and S. Talluri, “Knowledge Diversity, Turnover, and Organizational-Unit Productivity: An Empirical Analysis in a Knowledge-Intensive Context,” Production and Operations Management Society, Vol.23, No.8, pp. 1332-1351, 2014.

- [17] H. W. Turnbull (Ed.), “The Correspondence of Isaac Newton, Volume I: 1661-1675,” Cambridge University Press, 1959.

- [18] J. A. Schumpeter, “Theorie der Wirtschaftlichen Entwicklung,” Duncker und Humblot, 1926 (in German).

- [19] C. Macilwain, “What science is really worth,” Nature, Vol.465, pp. 682-684, 2010.

- [20] J. Lane and S. Bertuzzi, “Measuring the Results of Science Investments,” Science, Vol.331, pp. 678-680, 2011.

- [21] G. Eason, B. Noble, and I. N. Sneddon, “On certain integrals of Lipschitz-Hankel type involving products of Bessel functions,” Philosophical Trans. of the Royal Society A, Vol.247, pp. 529-551, 1955.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 Internationa License.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 Internationa License.