Review:

Evolution of Risk-Informed Land Use Regulations and Controls in Japan

Ritsuko Yamazaki-Honda*,**,†

*Land Institute of Japan

1-16-17 Toranomon, Minato-ku, Tokyo 105-0001, Japan

**National Research Institute for Earth Science and Disaster Resilience

Tsukuba, Japan

†Corresponding author

Land use regulations and controls in Japan have evolved in response to the needs and changes in the social background, as well as experiences of substantial disaster losses and damage. With the unprecedented scenario of an aging and depopulating society, as well as impacts of climate change: Target hazards have been expanded in terms of hazard type, disaster cause, and assumed scale. Target area designation has been expanded to include presumed affected areas, and regulated development and construction have been expanded to reduce exposure to disaster risk. More recently, necessary soft measures such as securing warning and evacuation systems have been additionally integrated. Despite the advancement of risk-informed land use regulations and controls in Japan, their practical implementation has been challenged due to social, institutional, and legal constraints. In practice, area designation has not been fully implemented due to insufficient capacities in terms of technical and financial resources at the local level. Although land use restrictions have promoted relocation and retrofit of buildings, they do not have an immediate effect to change exposure; therefore, a spatial master plan of disaster risk reduction with a timeline is imperative. While the government improves risk information and communication, people and society, as recipients of information, should strengthen their capacity to understand risk at all times and take necessary actions in times of disaster, through a multi-hazard approach in a multi-stakeholder framework. In the long run, systems are required that could transform the entire national land structure into a more resilient, “autonomous, decentralized, and coordinated” structure from a broader perspective.

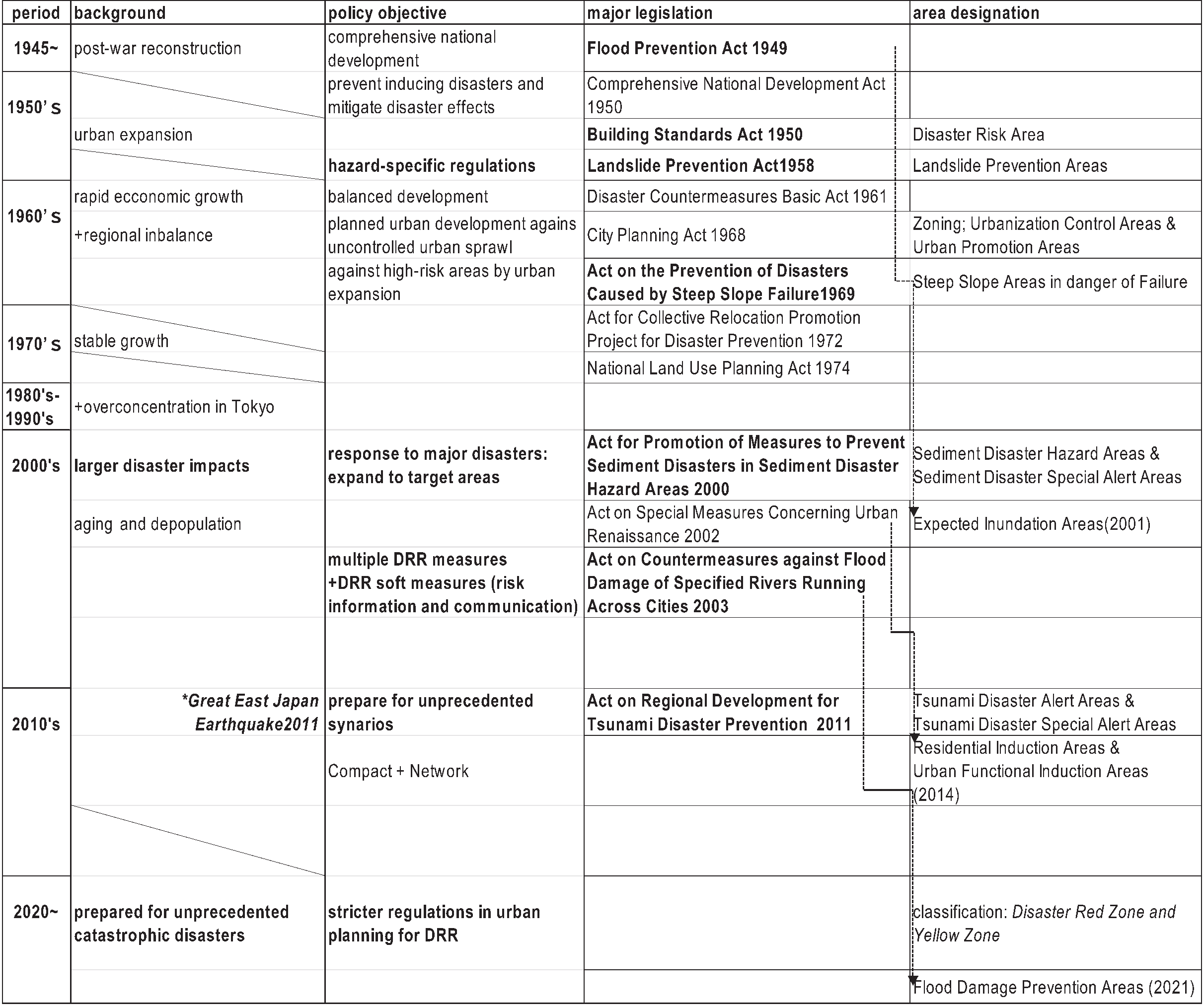

Chronological table and overview of land use regulations and controls for DRR

- [1] United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR), “Global assessment report on disaster risk reduction 2025 (GAR2025),” 2025. https://www.undrr.org/gar/gar2025 [Accessed June 1, 2025]

- [2] United Nations, “Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction 2015–2030,” 2015. https://www.preventionweb.net/files/43291_sendaiframeworkfordrren.pdf [Accessed April 1, 2025]

- [3] UNDRR, “Global assessment report on disaster risk reduction 2019 (GAR2019),” 2019. https://www.undrr.org/publication/global-assessment-report-disaster-risk-reduction-2019 [Accessed June 1, 2025]

- [4] Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) and Global Initiative on Disaster Risk Management (GIDRM), “Risk-informed development: Why it matters,” 2023. https://www.preventionweb.net/publication/risk-informed-development-why-it-matters [Accessed June 1, 2025]

- [5] N. Kiuchi, “On building and land use management regarding flood risks,” J. of the City Planning Institute of Japan, Vol.54, No.3, pp. 923-930, 2019 (in Japanese). https://doi.org/10.11361/journalcpij.54.923

- [6] H. Makino and Y. Asahina, “Characteristics of the act for prevention of disasters due to collapse of steep slopes seen from its aim and roles act played in nonstructural measures against sediment disasters,” J. of Japan Society of Erosion Control Engineering, Vol.68, No.4, pp. 28-36, 2015 (in Japanese). https://doi.org/10.11475/sabo.68.4_28

- [7] Y. Kawakami, “The Transition of Land Planning,” Kajima Publishing, 2008 (in Japanese).

- [8] A. Yamanome, “Reforms in the Legal System of Land Management,” Yuhikaku Publishing Co.,Ltd., 2022 (in Japanese).

- [9] C. Kodama and A. Kubota, “Study on the idea of land use regulation focusing on Article 39 of the building standards law,” J. of the City Planning Institute of Japan, Vol.48, No.3, pp. 201-206, 2013 (in Japanese). https://doi.org/10.11361/journalcpij.48.201

- [10] Ministry of Land Infrastructure Transport and Tourism (MLIT), “Examples of designated disaster risk areas attributed to flooding, etc.,” 2020 (in Japanese). https://www.mlit.go.jp/jutakukentiku/build/content/001362907.pdf [Accessed June 1, 2025]

- [11] MLIT River Council, “The report on the legal system for comprehensive sediment disaster prevention,” February 3, 2000 (in Japanese). https://www.mlit.go.jp/river/shinngikai_blog/past_shinngikai/shinngikai/shingi/000203index.html [Accessed April 1, 2025]

- [12] MLIT, “Sediment disaster hazard areas under the act for sediment disaster prevention,” 2021 (in Japanese). https://www.mlit.go.jp/river/sabo/sinpoupdf/gaiyou.pdf [Accessed April 1, 2025]

- [13] MLIT, “Partial amendment of act for promotion of measures to prevent sediment disasters in sediment disaster hazard areas,” 2021 (in Japanese). https://www.mlit.go.jp/mizukokudo/sabo/kaiseidosyahou.html [Accessed April 1, 2025]

- [14] M. Kawai, “Twenty years of the basic guidelines for sediment disaster prevention,” J. of Japan Society of Erosion Control Engineering, Vol.74, No.3, pp. 49-59, 2021 (in Japanese). https://doi.org/10.11475/sabo.74.3_49

- [15] Y. Yanada, “Water-related disasters and land use regulation,” The J. of the Land Institute, Vol.31, No.3, pp. 3-11, 2023 (in Japanese). https://www.lij.jp/html/jli/jli_2023/2023summer_p003.pdf [Accessed April 1, 2025]

- [16] MLIT, “Partial amendment of the flood prevention act,” May 2015 (in Japanese). https://www.mlit.go.jp/river/shinngikai_blog/shaseishin/kasenbunkakai/bunkakai/dai52kai/siryou3-2_01.pdf [Accessed April 1, 2025]

- [17] MLIT, “Abstract: Act on regional development for tsunami disaster prevention enacted,” 2011 (in Japanese). https://www.mlit.go.jp/common/001233095.pdf [Accessed April 1, 2025]

- [18] H. Watanabe and E. Itoigawa, “On residents’ acceptance factors for designation of alert area for tsunami disaster and measures for designation promotion – Case study at Toi Area in Izu City –,” J. of Institute of Social Safety Science, November 2020 (in Japanese). https://doi.org/10.11314/jisss.37.57

- [19] S. Araki, K. Magake, R. Kimura, and N. Akita, “The establishment process and philosophy of the disaster prevention collective relocation promotion project,” J. of the City Planning Institute of Japan, Vol.58, No.3, pp. 819-826, 2023 (in Japanese). https://doi.org/10.11361/journalcpij.58.819

- [20] E. Matsumoto and M. Ubaura, “A study on designation disaster hazard area after the Great East Japan Earthquake,” J. of the City Planning Institute of Japan, Vol.50, No.3, pp. 1273-1280, 2015 (in Japanese). https://doi.org/10.11361/journalcpij.50.1273

- [21] Y. Kaneyama, O. Murano, and H. Kato, “Land use transition and utilization in disaster hazard areas after the Great East Japan Earthquake: A case study of the affected areas in Miyagi Prefecture,” J. of Institute of Social Safety Science, No.37, pp. 41-50, 2024 (in Japanese). https://doi.org/10.11314/jisss.45.41

- [22] National Land Development Council, “Water-related disaster risk reduction considering climate change – Transition to river basin disaster resilience and sustainability by all –,” Council Report, July 2020. https://www.mlit.go.jp/river/kokusai/pdf/pdf23.pdf [Accessed April 1, 2025]

- [23] S. Nigo, “Water-related disasters and land use – Living arrangements,” The J. of the Land Institute, Vol.31, No.3, pp. 12-29, 2023 (in Japanese). https://www.lij.jp/html/jli/jli_2023/2023summer_p003.pdf [Accessed April 1, 2025]

- [24] A. Nishimura, S. Maeda, and T. Mori, “Ordinance for the creation of a safe and secure town based on a history of flood damage (Hidaka village ordinance),” Technical and Research Presentation Meeting of the MLIT Shikoku Regional Development Bureau, 2023 (in Japanese). https://www.skr.mlit.go.jp/kikaku/kenkyu/r5/ronbun/I-41.pdf [Accessed April 1, 2025]

- [25] MLIT, “Grand design of national spatial development towards 2050,” 2014 (in Japanese). https://www.mlit.go.jp/common/001047113.pdf, (English flyer: https://www.mlit.go.jp/common/001088248.pdf) [Accessed June 1, 2025]

- [26] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), “OECD territorial reviews: Japan 2016,” 2016. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/oecd-territorial-reviews-japan-2016_9789264250543-en.html [Accessed June 1, 2025]

- [27] Cabinet Secretariat, “Fundamental plan for national resilience,” 2014, 2018, and 2023 (in Japanese). https://www.cas.go.jp/jp/seisaku/kokudo_kyoujinka/kihon.html, (English 2018ver https://www.cas.go.jp/jp/seisaku/kokudo_kyoujinka/index_en.html) [Accessed June 1, 2025]

- [28] MLIT, “National spatial strategies,” 2015 and 2023 (in Japanese). https://www.mlit.go.jp/kokudoseisaku/kokudokeikaku_fr3_000003.html, (English 2015 ver. https://www.mlit.go.jp/common/001127196.pdf) [Accessed June 30, 2025]

- [29] National Land Agency, “4th comprehensive national development plan,” 1987 (in Japanese). https://www.mlit.go.jp/common/001135927.pdf [Accessed June 1, 2025]

- [30] MLIT, “Location normalization plan and compact plus network,” 2024 (in Japanese). https://www.mlit.go.jp/en/toshi/city_plan/compactcity_network.html [Accessed April 1, 2025]

- [31] MLIT, “Guideline (basic): Location normalization plan,” Ver.April 2024 (in Japanese). https://www.mlit.go.jp/en/toshi/city_plan/content/001741220.pdf [Accessed April 1, 2025]

- [32] K. Kita, “Review of development regulations in hazard areas – The 2020 amendment of the city planning act etc.,” The J. of the Land Institute, Vol.28, No.3, pp. 45-60, 2020 (in Japanese). https://www.lij.jp/html/jli/jli_2020/2020summer_p045.pdf [Accessed April 1, 2025]

- [33] MLIT, “City planning operation guidelines, March 2025,” (in Japanese). https://www.mlit.go.jp/toshi/city_plan/content/001880861.pdf [Accessed April 1, 2025]

- [34] S. Okitsu, K. Kanemitsu, and S. Asano, “Present condition and problem of treatments of disaster hazard areas in residence induction areas of location normalization plan – Focus on four prefectures (Gifu, Shizuoka, Aichi, Mie) of Tokai region –,” AIJ J. Technol. Des., Vol.27, No.66, pp. 937-942, 2021 (in Japanese). https://doi.org/10.3130/aijt.27.937

- [35] Nagoya City, “Nagoya city coastal disaster prevention area building regulations,” Ver.2024, March 1961 (in Japanese). https://www.city.nagoya.jp/jutakutoshi/cmsfiles/contents/0000011/11898/joureiR6.pdf [Accessed April 1, 2025]

- [36] R. Sato et al., “Research on plan updates based on trends in urban consolidation after the formulation of location optimization plans,” AIJ J. Chugoku Branch. Des., No.47, pp. 746-749, 2024 (in Japanese). https://doi.org/10.60442/aijchugoku.47.0_746

- [37] MLIT, “National land digital information download site,” (in Japanese). https://nlftp.mlit.go.jp/ksj/index.html [Accessed April 1, 2025]

- [38] MLIT, “Real estate information library,” (in Japanese). https://www.reinfolib.mlit.go.jp/map/ [Accessed April 1, 2025]

- [39] MLIT, “Future policy for the development and provision of national land digital information,” 2024 (in Japanese). https://www.mlit.go.jp/tochi_fudousan_kensetsugyo/chirikukannjoho/content/001756437.pdf [Accessed April 1, 2025]

- [40] MLIT, “Guidance on relocation for disaster risk reduction and community development,” Ver.2025 (in Japanese). https://www.mlit.go.jp/toshi/content/001515251.pdf [Accessed June 1, 2025]

- [41] MLIT, “Guideline for city planning informed by water-related disaster risks,” 2021 (in Japanese). https://www.mlit.go.jp/toshi/city_plan/content/001354421.pdf [Accessed June 1, 2025]

- [42] M. Ishiwatari et al., “Comparative study between Japan and US on relocation program of reducing disaster risks,” J. of Regional Development Studies, Vol.23, pp. 31-42, 2020 (in Japanese). http://id.nii.ac.jp/1060/00011807/ [Accessed July 11, 2025]

- [43] F. Ranghieri and M. Ishiwatari, “Learning from megadisasters: Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake,” World Bank, 2014. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/18864 [Accessed June 11, 2025]

- [44] E. Bower and S. Weerasinghe, “Planned relocation in Asia,” Platform on Disaster Displacement, 2021. https://www.preventionweb.net/media/75990 [Accessed July 11, 2025]

- [45] R. Shiraishi, “(Pre-Disaster) Group relocation policy to enable participatory planning – Comparing cases of the Philippines and Japan,” City Planning Review, Vol.369, pp. 118-119, 2024. https://www.cpij.or.jp/com/edit/cpr369-advance/23-shiraishi.pdf [Accessed July 11, 2025]

- [46] MLIT, “A study of risk awareness among homebuyers of flooding,” PRI Review, Vol.83, 2025 (to be published), (in Japanese). https://www.mlit.go.jp/pri/kikanshi/pdf/2025/83_11.pdf [Accessed July 11, 2025]

- [47] German Red Cross, IFRC Red Cross and Red Crescent Climate Centre, “Business relocation as an urban early action: Lessons and challenges from a simulation in the Philippines,” 2022. https://www.anticipation-hub.org/news/a-new-case-study-on-relocating-businesses-as-an-urban-early-action-in-the-philippines [Accessed July 11, 2025]

This article is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 Internationa License.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 Internationa License.